Out of the skies

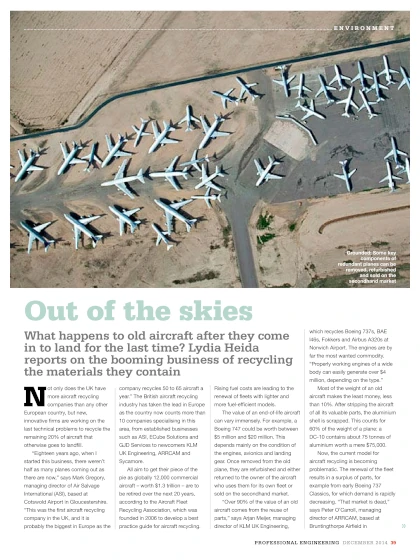

What happens to old aircraft after they come in to land for the last time? Lydia Heida reports on the booming business of recycling the materials they contain.

Not only does the UK have more aircraft recycling companies than any other European country, but new, innovative firms are working on the last technical problems to recycle the remaining 20% of aircraft that otherwise goes to landfill.

“Eighteen years ago, when I started this business, there weren’t half as many planes coming out as there are now,” says Mark Gregory, managing director of Air Salvage International (ASI), based at Cotswold Airport in Gloucestershire. “This was the first aircraft recycling company in the UK, and it is probably the biggest in Europe as the company recycles 50 to 65 aircraft a year.”

The British aircraft recycling industry has taken the lead in Europe as the country now counts more than 10 companies specialising in this area, from established businesses such as ASI, ECube Solutions and GJD Services to newcomers KLM UK Engineering, ARRCAM and Sycamore.

Best practice

All aim to get their piece of the pie as globally 12,000 commercial aircraft – worth $1.3 trillion – are to be retired over the next 20 years, according to the Aircraft Fleet Recycling Association, which was founded in 2006 to develop a best practice guide for aircraft recycling. Rising fuel costs are leading to the renewal of fleets with lighter and more fuel-efficient models.

The value of an end-of-life aircraft can vary immensely. For example, a Boeing 747 could be worth between $5 million and $20 million. This depends mainly on the condition of the engines, avionics and landing gear.

Once removed from the old plane, they are refurbished and either returned to the owner of the aircraft who uses them for its own fleet or sold on the secondhand market.

“Over 90% of the value of an old aircraft comes from the reuse of parts,” says Arjan Meijer, managing director of KLM UK Engineering, which recycles Boeing 737s, BAE l46s, Fokkers and Airbus A320s at Norwich Airport. The engines are by far the most wanted commodity. “Properly working engines of a wide body can easily generate over $4 million, depending on the type.”

Increase recycling rates

Most of the weight of an old aircraft makes the least money, less than 10%. After stripping the aircraft of all its valuable parts, the aluminium shell is scrapped. This counts for 60% of the weight of a plane: a DC-10 contains about 75 tonnes of aluminium worth a mere $75,000.

Now, the current model for aircraft recycling is becoming problematic. The renewal of the fleet results in a surplus of parts, for example from early Boeing 737 Classics, for which demand is rapidly decreasing.

“That market is dead,” says Peter O’Carroll, managing director of ARRCAM, based at Bruntingthorpe Airfield in Leicestershire.

To improve the business model, technological challenges need to be tackled, such as the recycling of the complex plastics from the interior, the proper separation of aluminium alloys, and the recycling of carbon fibre.

This is also important to increase the current recycling rate of aircraft, which lies around 80-85%, to 95% or higher, to stay in tune with the directives for vehicle recycling. Currently, the vast majority of materials that make up aircraft cabin interiors are sent to landfill.

First of its kind

To help solve this problem, SD Aviation opened a facility for recycling aircraft interiors last January. Located in Buckinghamshire, it is the first of its kind in Europe.

“Everything within that cabin we can recycle, from carpets, seats, luggage compartments, toilets to galleys,” says Aaron Day, managing director of SD Aviation, who has secured $10 million worth of new business this year.

“The biggest challenge has been the side-walls, galleys, ceiling and the floor that is made out of Nomex board.” This is a flame-resistant meta-aramid polymer, which is used to create honeycomb structures.

“We can melt that material down and the liquid we gain from that can be put into concrete or a sort of Lego brick to construct alternative accommodation for refugee camps and homes in Third World countries. (...)

Publication: Professional Engineering Magazine

Date: December 2014

Would you like to read the entire article?

VIEW FULL STORYObstakels voor cleantech

Read More

Boom time for carbon fibre recycling

Nanomaterials: a new threat to the recycling industry?

Interested in working together?

I'd love to hear from you.